On a snowy December night in 2010, the Staying Connected Initiative led a community visioning exercise with stakeholder groups and local officials representing Ava, Steuben, and Western, three small towns in the Tug Hill – Adirondacks linkage in New York. Despite the bad weather, the small town hall was packed with landowners, snowmobilers, birders, loggers, farmers, hikers, hunters, anglers, ATVers, and local people from all walks of life.

The 25 participants, guided by a Staying Connected facilitator, divided up into small groups, hunched over local maps, and began marking places they cared about and valued most within their communities.

“We asked a single question: ‘What do you love about living in your town?’ And in doing so, we made it very transparent that we were including all perspectives and that everyone’s view was equally valid,” remembers Leslie Karasin, Program Manger for the Adirondack Program of the Wildlife Conservation Society. “We weren’t trying to set priorities, discuss the merits of wildlife connectivity, or do land use planning. We merely wanted to document the places that people love in their towns, and find out why they care about them.”

The townspeople quickly warmed to the process: “Some said, ‘I love the quiet or wildlife sightings here, or I love to ski, hunt, or fish there.’ Others said, ‘I really love the economic opportunities provided here, or the community feel of the downtown.’ We got a huge range of responses,” recalls Jens Hilke, the Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department biologist who facilitated the meeting.

The exercise conducted that winter night is formally known as Community Values Mapping, an innovative new conservation technique being implemented by Staying Connected. “It’s a way to create conversations in communities around the shared values that exist between people,” rather than focusing on what divides them, says Karasin. “For me it was exciting to apply the tool and see its potential for finding common ground between diverse interest groups.”

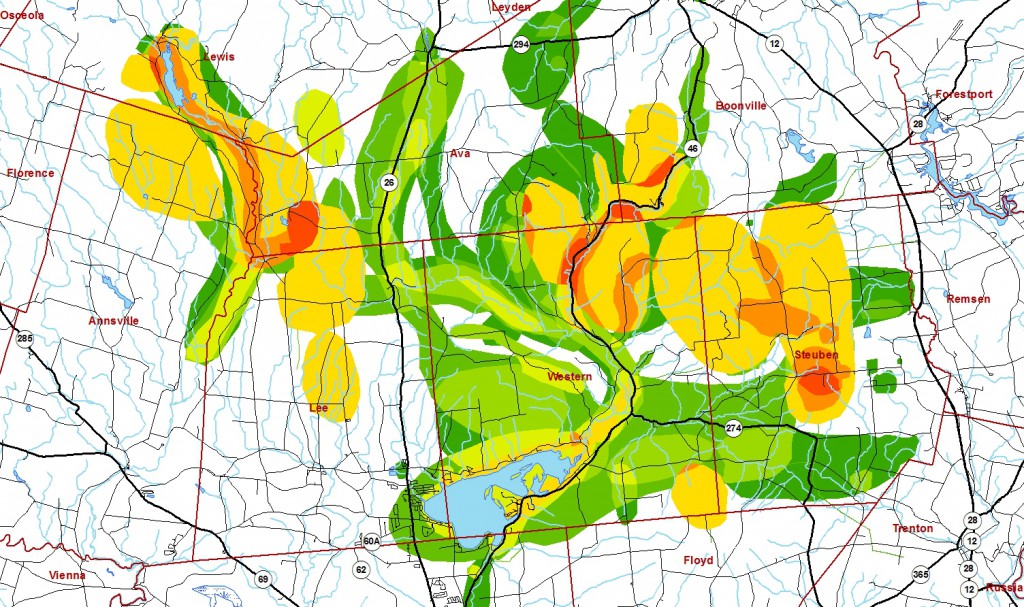

The groundwork for this particular Community Values Mapping session had been laid more than a year earlier. In 2009, the Staying Connected Initiative had modeled and mapped the wildlife linkages connecting New York’s Tug Hill, a 2,100 square mile upland of largely unbroken northern hardwood forest, and the Adirondack Mountains, with its 2.3 million acre Forest Preserve.

The most endangered linkage they discovered was a roughly 20-mile-long wildlife corridor that crossed the Black River Valley and included the tiny New York towns of Ava, Western, Steuben, Boonville, Forestport and Remsen.

“We noticed right away that those towns had a lot in common,” says Tug Hill Commission Associate Director of Natural Resources Katie Malinowski. “They’re all in northern Oneida County. They share valley topography, many of the same sorts of development pressures, are mostly rural, historically with lots of agricultural land. The local people typically shop in the same places, often know each other, and have similar attitudes,” including suspicions concerning outside conservation efforts and worries about inappropriate development altering the rural character of their towns.

“We noticed right away that those towns had a lot in common,” says Tug Hill Commission Associate Director of Natural Resources Katie Malinowski. “They’re all in northern Oneida County. They share valley topography, many of the same sorts of development pressures, are mostly rural, historically with lots of agricultural land. The local people typically shop in the same places, often know each other, and have similar attitudes,” including suspicions concerning outside conservation efforts and worries about inappropriate development altering the rural character of their towns.

A group of five Staying Connected partners – the Wildlife Conservation Society, The Nature Conservancy, Tug Hill Tomorrow Land Trust, Tug Hill Commission, and Northern Oneida County Council of Governments – went to work to implement the Initiative’s three-pronged strategy for maintaining linkages, which includes land protection, local land use planning, and technical assistance to local organizations.

Community Values Mapping was chosen as a key first step for engaging local towns, with one session planned for Ava, Steuben and Western in 2010, and a second planned for Boonville, Forestport and Remsen late in 2012.

The Community Values Mapping process began well before the actual meetings. “A vast majority of the work is in outreach done ahead of time by our local partners to insure all the constituencies are well represented on the night of the mapping activity,” says Hilke. “In our case we worked with the Tug Hill Commission and the circuit riders of the Northern Oneida County Council of Governments. They combed the communities, inviting a diverse cross-section of town residents to the events.”

Geraldine Ritter, a circuit rider very familiar with the residents of Ava, Western, and Steuben, was very happy with the resulting Community Values Mapping session. Despite the diverse views represented, participants “were surprised that all of the small groups came up with roughly the same information on their maps,” she recalls. “People agreed that the interactive exercise was very useful. One big plus was that they got to know people they didn’t know from other towns, and to understand what was important to adjoining communities.” The process also helped residents realize the value of what they have in their communities. Many agreed that Staying Connected might offer good tools for developing conservation guidelines in the future.

After the Ava, Steuben and Western meeting, Staying Connected merged all the data collected into a single document, mapping all the values that had been noted by attendees.

“The town of Ava soon incorporated the map into their comprehensive plan, along with statements referencing the importance of wildlife corridors,” reports Malinowski. That language includes ways to preserve habitat through site plan and subdivision review, and recommends minimum maintenance road designations to help protect wildlife. “Looking ahead, if the town implements zoning based on their comprehensive plan, then we can get very specific about recommending connectivity options,” Malinowski says.

The towns of Western and Steuben are still working on their comprehensive plans, though one of them has used the Community Values Mapping data to help officials focus on what’s important in their towns concerning the passage of land use updates. The results of the 2012 Community Values Mapping session in Boonville, Forestport and Remsen have yet to unfold. The town of Trenton, at the edge of the linkage, has also adopted connectivity language into its comprehensive plan.

Community Values Mapping is very useful in creating a baseline for land use planning. “Figuring out where a community wants to go in the future depends a lot on what community members value right now,” Hilke says. “The Community Values Mapping activity is an excellent way of bringing people into, and involving them early, in conservation planning.” It also shows Staying Connected where community consensus already exists regarding valued natural places, and where those areas overlap with ecologically important areas for habitat connectivity, an indication of potential community buy-in for conservation.

Community Values Mapping is just one of many Staying Connected efforts underway in the Tug Hill – Adirondacks linkage. The partners have developed a series of technical handbooks for planners called, “Make Room for Wildlife,” a printed resource that lays out options for appropriate development while minimizing wildlife impacts. The handbook has been presented to dozens of communities and landowners in the region.

In addition, the partners have joined with the N.Y. Department of Transportation (NYDOT) and two local highway departments to identify potential mitigation projects to enhance wildlife movement across roads. “Road kill is to no one’s advantage, not for the state, towns or wildlife,” notes Geraldine Ritter who has ridden with highway superintendents in an attempt to locate wildlife crossing hotspots. “Staying Connected has used its models to help towns pinpoint where animals are crossing, and is taking action to recommend signage, fencing, or underpass modifications for animal use.”

The partners are currently awaiting NYDOT engineer approval of a “critter walk,” a wildlife shelf added to a key culvert on Route 12/22 – a major road barrier to animal movement in the Black River Valley. Elsewhere, The Nature Conservancy has secured funding to up-size an important culvert to enhance Tug Hill – Adirondacks connectivity.

A citizen science tracking program is also underway in this linkage. WildPaths uses local volunteers to generate data on 30 miles of priority roadways in the Black River Valley to inform local land use and transportation decisions. WCS’ Adirondack Program Director, Zoё Smith, describes the benefits of WildPaths. “Using citizen scientists allows us to collect important data as well as build shared knowledge and interest in the landscape used by both people and wildlife”.

Targeted land conservation efforts have also proven successful. ”We’ve primarily been working with donated conservation easements through the Tug Hill Tomorrow Land Trust,” says Dirk Bryant, Director of Conservation Programs for the Adirondack Chapter of The Nature Conservancy. “The goal, as in other linkages, is to protect significant habitat stepping stones. We’ve been focusing on a five-mile stretch of the Black River Valley where there is a lot of potential for second home development. Today, most of that area is largely forested, so there is a real opportunity to prevent the valley from becoming a barrier to wildlife.” Over the last three years the Staying Connected partners have protected more than 1,000 acres in the Tug Hill – Adirondacks linkage.

“One of the best, most unexpected, things to come out of Staying Connected is that we’ve formed excellent relationships with the other partners,” says Tug Hill Tomorrow Land Trust Executive Director Linda Garrett. “We didn’t have an opportunity to work with some of these groups before, and it’s definitely a positive. Now that we’ve got the momentum going, we hope to work with the linkage communities to raise awareness even further.” Garrett is especially hoping to develop a Staying Connected curriculum for local children at an environmental center in Boonville. “Getting the word out to kids is always a good way to build awareness for the future,” she says. “We’re doing everything we can to move Staying Connected forward in our communities. Maintaining wildlife connectivity makes sense to local people and we want to see the Initiative continue.”

“Community Values Mapping is a key first step in working with local communities, because the Staying Connected partners send a clear message: We care about what you think,” concludes Hilke. “Staying Connected isn’t just about connecting wildlife. It is about connecting people. Linking people to each other, to the landscape, and to wildlife.